Psychological Barriers to Communication

Psychological barriers to communication are often invisible but incredibly powerful. They shape the way we listen, speak, and connect. Have you ever wondered why a simple message turns into a misunderstanding, or why you sometimes hold back your true thoughts? The answer often lies in psychological barriers to communication—internal blocks like stress, bias, low confidence, and emotional baggage. If left unchecked, these barriers can keep us from building trust and having honest conversations. Recognizing and addressing psychological barriers to communication is the first step to better relationships at home, at work, and everywhere in between.

What Are Psychological Barriers to Communication?

Psychological barriers to communication are the internal obstacles that cloud our thinking, distort our messages, and make it hard to connect. Unlike physical noise or language differences, these barriers come from within. They include emotional interference, biases, low self-esteem, anxiety, past experiences, and even the fear of being judged.

Everyone faces psychological barriers to communication at some point. They show up as hesitation, misunderstandings, or even silence. For example, a person with low confidence might avoid speaking up, while someone anxious could misread a harmless comment as criticism.

Major Psychological Barriers

Emotional States and Psychological Noise

Emotions can be both allies and obstacles. When we’re calm and happy, it’s easy to listen and share ideas. But strong feelings—like anger, sadness, or stress—can quickly create psychological noise. This “noise” acts like static on a phone call, making it tough to get the message across.

Imagine trying to explain something while feeling anxious about a deadline. Even a neutral question from a coworker can sound like criticism. This is psychological noise in action. Mindfulness and emotional regulation skills, such as pausing to breathe or naming your emotions, help reduce this static and make communication clearer.

Biases, Stereotypes, and Selective Perception

Our brains love shortcuts, but sometimes these shortcuts block our view. Biases—like confirmation bias—lead us to notice only information that supports what we already believe. Stereotypes and attribution errors make us judge others quickly, without seeing the whole picture. For example, if a manager assumes a quiet team member is uninterested, they may ignore valuable ideas.

Stereotype threat is a related problem. People from minority or underrepresented groups may worry about confirming negative stereotypes, which can cause them to stay silent or feel extra pressure.

Self-Esteem, Confidence, and Trust

Low self-esteem is a common psychological barrier to communication. If you don’t believe your ideas are valuable, you may avoid sharing them altogether. Self-confidence affects how you speak, how much you contribute, and even how you interpret others’ words.

Trust and psychological safety play a huge role, too. When people feel safe, they speak honestly and listen openly. In contrast, when there’s fear of judgment, people hide mistakes, avoid tough topics, or just stop talking.

Mental Health and Past Experiences

Mental health issues like anxiety, depression, or trauma make communication more difficult. Stress can overload our brains, making it hard to focus or interpret signals accurately. Past negative experiences, especially if they involved rejection or ridicule, can leave emotional scars. These scars may trigger defensive reactions, silence, or misinterpretation in new conversations.

If you notice these patterns, seeking professional help or using self-assessment tools like journals or checklists can be a great first step to break the cycle.

Social Identity, Group Membership, and Intersectionality

Communication doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Our identity—race, gender, age, ability, and social status—shapes how we’re perceived and how comfortable we feel. In-group/out-group bias means we sometimes listen more closely to people “like us” and ignore or mistrust outsiders.

Intersectionality reminds us that some people face more than one barrier at a time. For example, a young woman of color with a disability may experience unique challenges that others don’t see. Understanding intersectionality helps us be more inclusive and sensitive in every conversation.

Attribution Errors and Emotional Baggage

It’s easy to blame others’ actions on personality instead of circumstances. This is known as the fundamental attribution error. For instance, if someone is late to a meeting, we might think they’re irresponsible rather than considering they had an emergency.

Emotional baggage from past misunderstandings can make us react defensively in new situations. Being aware of these patterns can help break the cycle.

Digital Psychological Barriers

Today, many conversations happen online—through email, chat, or video calls. Digital settings create new psychological barriers to communication. It’s easy to misread tone, miss nonverbal cues, or feel disconnected. Zoom fatigue, digital exclusion, and tech anxiety are all real. People may be afraid to speak up in a large video call or may misunderstand a short, text-only message.

Adapting to these challenges means being more intentional about clarity, tone, and inclusion online.

Measurement and Self-Assessment

The first step to overcoming psychological barriers is recognizing them. Organizations use climate surveys, feedback tools, and regular check-ins to spot problems early. Individuals can keep journals, ask for honest feedback, or use self-assessment quizzes to reflect on their own communication habits.

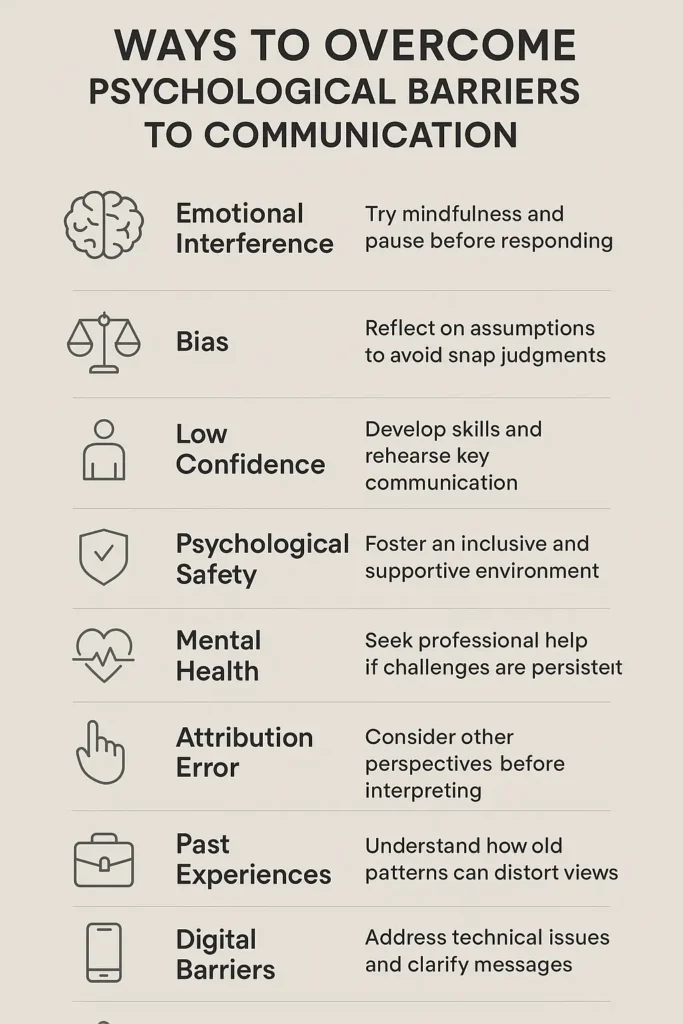

Strategies for Overcoming Psychological Barriers to Communication

Breaking psychological barriers takes awareness, practice, and patience. Here are some proven strategies:

Build Self-Awareness

Spend a few minutes each day reflecting on your feelings and reactions. Notice when you’re hesitant to speak or when you judge someone quickly. Journaling or mindfulness exercises can increase your self-awareness.

Practice Active Listening

Active listening means giving your full attention, nodding, making eye contact, and repeating back what you heard. This not only prevents misunderstandings but also builds trust.

Regulate Emotions

When emotions run high, pause. Take a deep breath or a short break. Mindfulness, deep breathing, or counting to ten can reset your mind for a more productive conversation.

Address Bias and Stereotypes

Challenge your own assumptions. Ask yourself, “Am I being fair?” Seek diverse perspectives and listen to people from different backgrounds.

Build Psychological Safety and Trust

Leaders should encourage questions and admit mistakes. Colleagues can show gratitude and respect for different viewpoints. Safe environments invite honest sharing and reduce the fear of judgment.

Encourage Self-Confidence and Growth

Acknowledge small wins and positive contributions. Encourage team members (and yourself) to try new things, even if it means making mistakes.

Support Mental Health

Promote resources for stress, anxiety, and depression—like counseling or support groups. Normalize asking for help. Encourage regular breaks and work-life balance.

Address Digital Barriers

Be extra clear in online communication. Use friendly greetings, clarify tone, and check in with quieter team members. Make sure digital meetings are accessible for everyone.

Psychological Barriers and Solutions

| Barrier Type | Solution | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional Interference | Mindfulness, emotional regulation | Calmer, clearer conversation |

| Bias and Stereotypes | Reflection, diverse input | Fairer, more open dialogue |

| Low Self-Esteem or Confidence | Encouragement, small wins | More participation |

| Lack of Psychological Safety | Safe spaces, open leadership | Honest, trusting teams |

| Mental Health Challenges | Support resources, counseling | Reduced stress, clarity |

| Attribution Error | Consider context, ask before judging | Better understanding |

| Past Negative Experiences | Self-reflection, awareness | Breaking old patterns |

| Digital Barriers | Clear communication, inclusive practices | Fewer misunderstandings |

| Intersectionality | Listen for unique challenges, adapt | More inclusive culture |

Real-Life Example

In a busy tech company, team members from different backgrounds struggled to share ideas in meetings. Some felt their comments would be dismissed, while others feared negative stereotypes. The company started weekly “safe space” meetings where everyone could speak freely, with no interruptions or judgments. Leadership offered regular feedback and recognized all contributions. Over time, team confidence grew, new ideas flowed, and misunderstandings dropped. This real-life example shows that breaking psychological barriers to communication leads to real results.

Conclusion

Psychological barriers to communication can hide in every conversation, but they don’t have to control us. From bias and stress to low confidence and digital confusion, these barriers are real—but so are the solutions. With self-awareness, active listening, support, and a commitment to fairness, you can build trust and have clearer, more honest conversations. Whether at work, at home, or online, overcoming psychological barriers to communication is the key to stronger relationships and lasting success.