Physiological barriers to communication

Physiological barriers to communication often go unnoticed, yet they can create some of the biggest hurdles in our everyday lives. Have you ever felt frustrated when someone doesn’t respond as expected—or maybe you struggle to follow a fast-paced conversation, especially in a noisy room? You’re not alone. These challenges aren’t always about attitude or effort; sometimes, they’re about how our bodies and brains process information. From hearing loss and vision impairment to chronic illness or neurodiversity, these barriers touch millions of people. If we want to communicate clearly and include everyone, it’s essential to understand what physiological barriers are, where they come from, and what can be done about them.

What Are Physiological Barriers to Communication?

Physiological barriers to communication are obstacles created by the body or brain that make sending, receiving, or processing messages difficult. These barriers can be physical, sensory, neurological, or even related to chronic health conditions or medication side effects. The key difference from psychological or language barriers? Physiological challenges stem from the way our bodies function—or sometimes, from the way they don’t function as expected.

Let’s break this down further. Imagine trying to join a conversation when you’re tired, in pain, or struggling to hear over background noise. Or maybe you’ve seen a friend with a stutter hesitate to speak up, even when they have valuable input. Barriers like these can make communication awkward, stressful, or even impossible unless others adjust their approach or the environment.

Some common examples include:

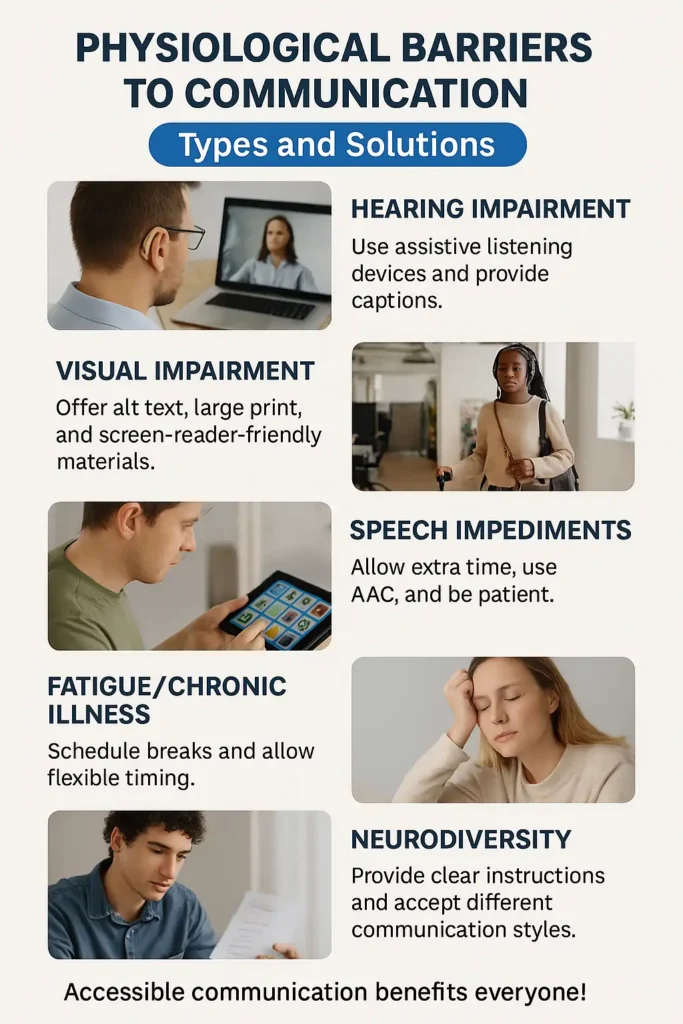

- Hearing impairments or auditory processing disorders

- Visual impairments

- Speech impediments or language production challenges

- Chronic illnesses and fatigue

- Neurological differences (neurodiversity)

- Medication side effects that slow thinking or speech

- Environmental factors such as noise, poor lighting, or lack of assistive devices

Understanding these barriers is the first step to finding solutions that work for everyone.

Hearing Impairments and Auditory Processing Disorders

One of the most widespread physiological barriers to communication is difficulty with hearing. It isn’t just about “being deaf.” Many people live with partial hearing loss, tinnitus, or auditory processing disorders—where the ears may be fine, but the brain struggles to make sense of sounds. According to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, around 15% of American adults experience some trouble hearing.

Hearing impairments can show up as:

- Needing the speaker to repeat themselves

- Missing important details in meetings

- Struggling with group conversations or background noise

- Reliance on lip reading or visual cues

Auditory processing disorder can be especially frustrating because it’s invisible. A person may “hear” perfectly but can’t distinguish between similar-sounding words or pick out a single voice in a noisy room.

Tips to reduce hearing-related barriers:

- Use assistive technology like hearing aids or FM systems

- Choose quieter spaces for conversations

- Offer written summaries or captions

- Face the person when speaking, and speak clearly—don’t shout

For workplaces, providing captioning for meetings or live events, and making sure digital content is accessible, helps bridge the communication gap for everyone.

Visual Impairments

Visual information is a huge part of how we connect—body language, facial expressions, slide presentations, and even the chat on a screen. For people with vision loss or blindness, these cues can be missed, creating significant physiological barriers to communication.

Vision challenges include:

- Partial or total blindness

- Low vision (difficulty seeing in dim light, recognizing faces, or reading)

- Color blindness, which can make charts or presentations confusing

These barriers impact not just reading but also social connection. A lack of visual feedback can make conversations less personal or more confusing. According to the Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB), about 2 million people in the UK alone live with sight loss.

Ways to make communication accessible:

- Use descriptive language and announce your presence in a group

- Provide alt text for images and high-contrast, large print materials

- Offer documents in accessible formats (braille, screen reader compatible)

- Describe key visuals during presentations

Digital accessibility isn’t just a “nice to have”—it’s a must for inclusive workplaces and public spaces.

Speech Impediments and Language Production Challenges

Speech impediments, such as stuttering, lisping, or conditions like aphasia, can create anxiety and frustration for both the speaker and the listener. These are classic physiological barriers to communication, sometimes resulting from birth, injury, neurological disease, or developmental differences.

Some common speech and language production challenges:

- Stuttering: Disrupts fluency and can lead to avoidance of speaking situations.

- Aphasia: Difficulty finding words, forming sentences, or understanding language, often due to stroke or brain injury.

- Dysarthria: Muscle weakness that affects the ability to speak clearly, often caused by neurological conditions like Parkinson’s disease.

- Articulation disorders: Problems with pronouncing certain sounds.

Speech-language pathologists are specialists who help people overcome these challenges with therapy and tools. Technology has also made a huge impact—there are now speech-generating devices, mobile apps, and even real-time feedback programs like Constant Therapy.

Support strategies include:

- Allow extra time for responses

- Use alternative communication (text, gestures, AAC devices)

- Don’t finish sentences for someone—be patient and encouraging

Chronic Illness, Fatigue, and Physical Health

Fatigue and chronic health conditions can act as powerful physiological barriers to communication. Conditions like multiple sclerosis, chronic fatigue syndrome, and autoimmune diseases can drain energy, slow thinking, and limit the stamina needed for conversation.

Other physical health issues can include:

- Muscle weakness affecting speech or sign language

- Pain distracting from conversation

- Respiratory conditions making it hard to speak for long

Side effects of medication can also play a role—some drugs cause drowsiness, memory issues, or slurred speech.

How to support communication in these cases:

- Schedule conversations for times when energy is highest

- Allow for breaks and use written follow-ups

- Recognize that slow responses aren’t lack of interest, but may reflect real physical limits

Neurodiversity: Embracing Different Brains

Neurodiversity covers a wide range of differences, from autism spectrum conditions to ADHD and acquired brain injuries. These differences can affect how people process sensory input, use language, or interpret nonverbal cues.

For instance, someone with autism may struggle with eye contact, tone of voice, or idioms, while a person with ADHD might find it hard to focus in a noisy environment. These are genuine physiological barriers to communication—not just personality quirks.

Inclusive communication practices:

- Avoid sarcasm or ambiguous language

- Provide written agendas and clear, concrete instructions

- Allow alternative ways to participate (typing, drawing, or using AAC devices)

- Be patient and check for understanding

Environmental and Systemic Barriers

Sometimes, the environment itself makes communication harder—think loud open-plan offices, poor lighting, lack of accessible technology, or rushed schedules. While these aren’t strictly physiological barriers, they interact with physical and sensory differences to make communication even tougher.

Tactics for improvement:

- Use quiet spaces for sensitive conversations

- Make sure meetings are accessible—offer interpreters, captions, or visual aids

- Practice universal design: materials should work for everyone, not just the majority

Legal Rights and Workplace Accommodations

Legal protections like the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and UK Equality Act require workplaces and public institutions to provide reasonable accommodations for people with physiological barriers to communication. This can mean providing assistive technology, allowing service animals, ensuring digital accessibility, or offering flexible work arrangements.

Employees have the right to request these supports, and employers are responsible for making sure communication is accessible for all team members.

The Power of Multi-Modal Communication

One powerful solution is to use multi-modal communication—combining spoken, written, visual, and tactile information. For example, sharing meeting notes, visual diagrams, and recorded audio together makes sure everyone can access the message in the format that works best for them.

Examples:

- Provide both a spoken explanation and a written summary

- Use tactile models or braille for hands-on learning

- Add subtitles to videos and offer audio descriptions

Family, Caregiver, and Community Support

Nobody overcomes physiological barriers to communication alone. Family members, caregivers, therapists, and community organizations all play crucial roles. They can help advocate for accommodations, model supportive communication, and provide tools and resources. Support groups offer a place to share experiences and solutions.

Encourage those facing communication challenges to reach out for help—sometimes the best ideas come from others who’ve “been there.”

Measurement, Early Intervention, and Professional Assessment

Regular screening and early assessment make a big difference, especially for children or anyone noticing new challenges. Audiologists, speech-language pathologists, occupational therapists, and other professionals can offer customized solutions.

Early intervention and ongoing measurement help people stay connected, maintain independence, and avoid the isolation that often accompanies communication difficulties.

Conclusion

Physiological barriers to communication touch every part of society—from classrooms and workplaces to families and public life. Recognizing these challenges is only the first step. When we combine practical solutions like universal design, legal rights, multi-modal communication, and the support of families and professionals, we can open the door to more meaningful and accessible connections for everyone.

If you or someone you know is struggling with physiological barriers to communication, don’t wait. Reach out to a speech-language pathologist, accessibility expert, or advocacy organization. Small changes can make a huge difference, and together, we can build a world where everyone’s voice is heard.